© Wonders of World Aviation 2015-

Part 18

Part 18 of Wonders of World Aviation was published on Tuesday 5th July 1938, price 7d.

This part included a central photogravure supplement showing landmarks from the air, illustrating the article on The Pupil Becomes a Pilot. The final section of the photogravure supplement illustrates a Goodyear airship landing. It illustrates the article How Airships Are Flown.

The Cover

This week’s cover shows a Supermarine Stranraer flying boat in flight near Eastleigh, Hampshire. This type of flying boat has two Bristol Pegasus X nine-cylinder radial air-cooled engines. The span of the flying boat is 85 feet, the length 54 ft 10-in and the height

21 ft 9-in.

Contents of Part 18

Survey in the Empire (Part 2)

This chapter describes the work of the air survey companies used throughout the British Empire. The article is concluded from part 17.

The article is the fourth in the series on Air Photography.

American and Canadian Pioneers

In 1907 there was formed at Halifax, Nova Scotia, the Aerial Experiment Association. The object of the association was to build a practical aeroplane which would carry a man and be driven through the air by its own power. The Association was not a commercial concern, but an association for the general pooling of ideas. It carried out invaluable work in the early days of American flying, and it provided aviation with one of its most romantic stories. This chapter describes the achievements of the Association and its members.

This chapter deals with that stage of the pupil’s career after he has taken his “A” licence and is ready for further dual instruction. This stage is known as “advanced dual” and includes instruction in landing, the use of the engine during the approach for a landing, forced landings in a cross-wind, cross-country flying and map-reading, the use of the compass and passenger-carrying.

This chapter is the fifth article in the series on Learning to Fly.

The Pupil Becomes a Pilot Photogravure Supplement - 2

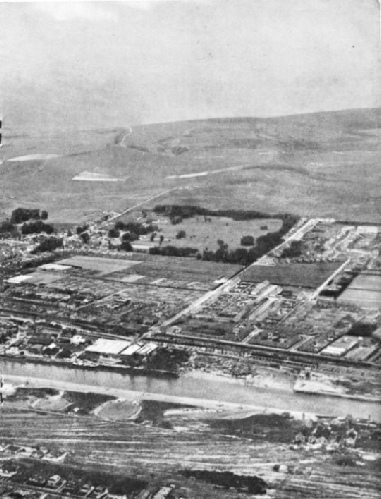

LARGE AREAS OF WATER such as rivers, harbours and the sea are the best features by which a pilot can locate his position. This picture shows a view of the country immediately east of Shoreham airport. The aircraft is a Jersey Airways Express Air Liner which has just left the aerodrome. Pilots of private aeroplanes give way to commercial aircraft whenever possible.

An airship pilot must be something of a Scientist: his knowledge of meteorology must be more than merely superficial. He must undergo a longer and more arduous period of training than a pilot of a heavier-

Aeroplanes of the Great War - 1

The Royal Naval Air Service and the Royal Flying Corps were using in 1914 aeroplanes both of home and of foreign origin. At that time, although there were numerous aircraft builders in Great Britain, there were few manufactures of aero engines. The aircraft of both Services were, therefore, powered almost exclusively by engines manufactured on the Continent. At the beginning of the war of 1914-1918 both flying Services were in a chrysalis stage, for aviation had not yet emerged as an effective arm. Admiralty and War Office departments responsible for the two air Services, the officers commanding units and the pilots themselves were all feeling their way towards the development of naval and military aviation. This chapter describes the machines of the RNAS and the RFC at the beginning of the war.

It is the first article in the series Aeroplanes of the Great War.

First Aviator to Fly the Channel (Part 1)

Great Britain’s traditional insularity was weakened if not destroyed in forty minutes on July 25, 1909, when Louis Bleriot became the first man to cross the English Channel in an aeroplane. Bleriot’s flight roused considerable interest, but for the most part it was regarded as little more than a rather daring exploit. Only a few people realized the deep significance of this feat; certainly the official mind of the day did not appreciate that this flight was to cause a profound change in defence tactics. This chapter shows that, although Bleriot’s fame rests on his cross-Channel flight, his other contributions to aviation were no less important. The article is concluded in part 19.

This article is the ninth in the series on Makers of Air History.

The Pupil Becomes a Pilot

Photogravure Supplement

CATHEDRALS OR CHURCHES WITH SPIRES make good landmarks from the air, and are shown on maps by a cross. From this view of Salisbury the pilot would verify where he was by noting the position of the cathedral in relation to the river crossed by the wide road in the foreground. By thus noting one feature in its relation to another the pilot avoids the possibility of mistaking one town, railway or other landmarks for another.