© Wonders of World Aviation 2015-

Part 2

Part 2 of Wonders of World Aviation was published on Tuesday 15th March 1938, price 7d.

This part included a colour plate showing a Miles Magister monoplane which accompanied the article on Learning to Fly.

There was also a central photogravure supplement showing various gliders which illustrated the article on Modern Soaring Flight.

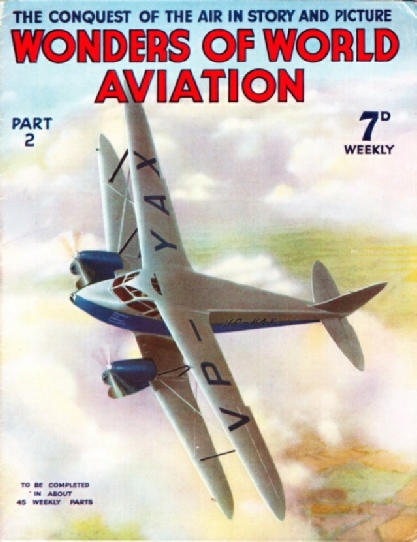

The Cover

There are no editorial notes about this cover which shows a De Havilland DH.90 Dragonfly of the Rhodesian and Nyasaland Airways.

According to the Aviation Safety Network database, this aircraft crashed near Gwelo, Southern Rhodesia, on 20 December 1938, nine months after this Part was published.

Contents of Part 2

Into the Stratosphere (Part 2)

The first ascent of over ten miles by Professor Auguste Piccard. This chapter is concluded from part 1.

The First English Aeronaut

James Sadler (1751-1828) gained the distinction of being the first Englishman to fly, and perhaps the first man in England to make serious contributions to the art of ballooning.

This is the first article in the series Makers of Air History.

Seaplanes and Their Work

Special types of aircraft developed for marine uses. Seaplanes may be divided into two principal classes: floatplanes and flying boats. The amphibian is a type which can alight on or take off from either land or water, and so may act as a landplane or a seaplane.

Modern Soaring Flight

Engineless flying in gliders and sailplanes. Although there is a school of thought which frowns on the art of gliding and soaring flight, it is linked historically with the beginnings of flight and since it provides a sport which attracts exponents throughout the world. The early glider experiments were the first steps to controlled heavier-than-air flight, and the coming of the internal combustion engine changed this dream into reality.

Modern Soaring Flight

Photogravure Supplement

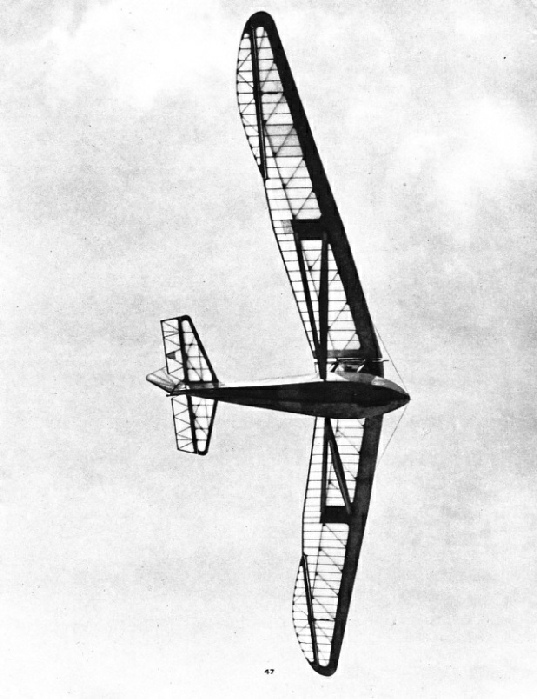

THE WINGS OF A SAILPLANE are covered partly with plywood, generally about 1½ millimetres thick, and partly with fabric. The wing has a main spar at the leading edge and a light spar or spars near the trailing edge. The main spar has to carry the bending moment caused by the forces on the wing.

Modern Soaring Flight: Photogravure Supplement

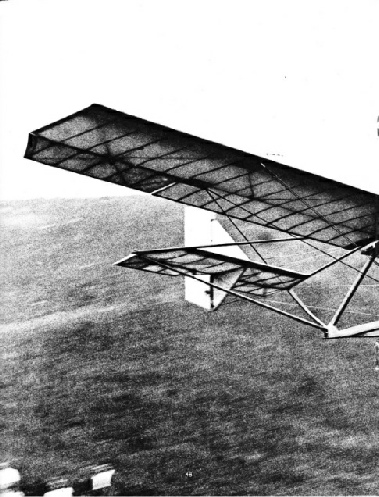

GLIDER BEING LAUNCHED by rubber rope. The rope falls off the hook when it has become loose, and the flier then glides down until his craft comes to rest on the skid, above which he is sitting.

Modern Soaring Flight:

Photogravure Supplement

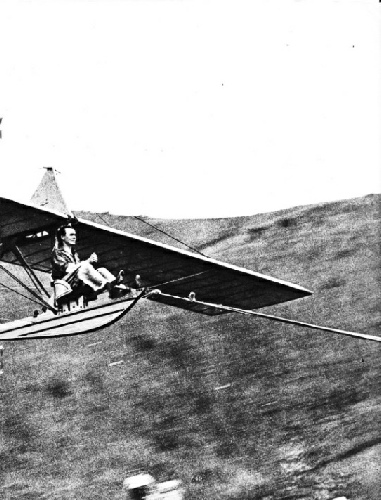

SOARING ABOVE THE LONGMYND, a hill near Church Stretton, Shropshire, is a sailplane named The Professor, from the Midland Gliding Club.

Evolution of the Aero Engine

The evolution of the aero engine is a fascinating story of progress and mechanical achievement.

Learning to Fly - 1

Preliminary instruction on the ground and in the air. Learning to fly is another branch of our subject of which this is the first chapter. This series of articles will cover a complete and up-to-date account of flying tuition and what it means today.

Round the World in Eight Days (Part 1)

How pilot and navigator encircled the earth from New York to New York. One of the most outstanding flights of recent years was that of the Winnie Mae, a small monoplane in which the late Wiley Post and Harold Gatty flew round the world in eight days sixteen hours. The chapter is concluded in part 3.

This is the first article in the series on Great Flights.