© Wonders of World Aviation 2015-

Part 37

Part 37 of Wonders of World Aviation was published on Tuesday 15th November 1938, price 7d.

This part included a colour plate showing Fighter Squadron Markings. This was one of the illustrations in the article on Air Defence Cadets.

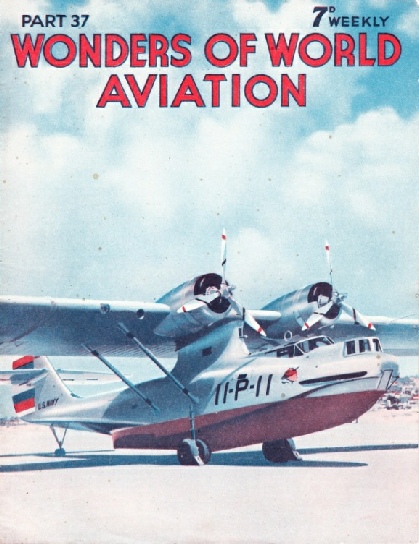

The Cover

The cover on this week’s Part shows one of the flying boats built by the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation for the United States Navy. As explained in the chapter “Patrol Boats of the Air”, which appeared in Part 35, Consolidated flying boats are built at San Diego, Califormnia, close to the United States naval base there. Final assemblies of these boats take place on large paved yards adjoining the San Diego factory. US Navy test pilots take over the flying boats after final assembly.

Contents of Part 37

Pageantry in the Air (Part 2)

Air Defence Cadets

Fighter Squadron Markings (colour plate)

Surveying New Airways

Major Edward Mannock, VC

Model Petrol-Driven Aeroplanes

The Russian Air Force

French Airships

The Hurricane Fighter

A Leader of British Aviation (Part 1)

Air Defence Cadets

This chapter gives an account of the origin of the Air Defence Cadet Corps. This corps was inaugurated by the Air League of the British Empire in 1938, with the object of providing a reserve of partly trained young men with some knowledge of aviation. Such a reserve would be of the greatest value in a national emergency. Cadets will be chosen by local committees; the age-limits will be between fourteen and eighteen. The Air League of the British Empire has undertaken to raise a minimum of 20,000 Air Defence Cadets throughout the country.

Major Edward Mannock VC

The life of Major Edward Mannock VC. Mannock was a born leader of men and a great fighter. At one time he attacked six enemy aircraft single-handed.

This is the sixth article in the series Epics of Service Flying.

The Hendon RAF Pageant (Part 2)

The concluding part of this chapter describing how the Royal Air Force display at Hendon improved year by year until its discontinuation after 1937.

The article is concluded from part 36.

Claude Grahame-White: a Leader of British Aviation (Part 1)

The work of Claude Grahame-White . He was the first person to show that a British pilot could compete with French experts.

The article is the seventeenth in the series Makers of Air History and is concluded in part 38.

Model Petrol-Driven Aeroplanes

This chapter on model petrol-driven aeroplanes, is certain to attract widespread interest. Duration models, described in a chapter in Part 35, have “motors” of twisted rubber. Petrol-driven models have miniature internal combustion engines. The cubic capacity of these engines normally vanes from 2.3 to 18 cc; a popular size is 6 cc. Model petrol-driven aircraft can fly at speeds ranging from 12 to 25 miles an hour.

Surveying New Airways

“Trail-blazing ” is a picturesque term which might legitimately be applied to the surveying of new air routes. The term, however, finds little favour with the commercial pilot and the commercial aviation company. They prefer the less colourful expression “survey flight”, as they take the attitude that the work involved is no more remarkable than any other

This point of view is strikingly exemplified in the attitude of Pan American Airways to air surveys. In this chapter, a description is given of the work of Pan American Airways in investigating the possibilities of ocean air routes generally and, in particular, of the route across the Southern Pacific Ocean from California to New Zealand. The work is regarded so much as a matter of routine, not only by the aviation companies but also by the general public, that in the United States, the home of publicity, the newspapers devoted very little space to accounts of Pan American’s three years of survey work in the Pacific.

After a year of preliminary research, an expedition set out in 1935. The expedition’s task was to make complete marine and weather surveys of various islands between Samoa and New Zealand, and to recommend sites for flying-boat bases, weather observation posts and radio stations, both for communication and for direction finding. Then followed two years of intensive research. Specialists went to various recommended bases and made detailed studies of the water, weather and winds. In the spring of 1937 one of the Pan American clipper flying boats made its survey flight.

The route finally chosen was from San Francisco to Hawaii, and thence to Kingman Reef, Samoa and Auckland, New Zealand. Kingman Reef is a coral island too small for habitation; so a ship was posted there as a temporary base. This ship was fully equipped with

radiotelephony and direction-finding apparatus, and it was staffed in the same way as a land base.

In contrast to the loneliness of the first stages of the survey flight, there are nearly a hundred islands between Samoa and New Zealand. The crew of the clipper took observations on many of these islands, charted them correctly and logged them as landmarks for future pilots flying on regular service.

The weather conditions varied greatly. The fliers ran into a snowstorm only 200 miles from the Equator. They met clouds and heavy rain between Kingman Reef and Samoa, and the aftermath of a cyclone between Samoa and Auckland. The whole flight was regarded as a routine affair. The captain of the clipper reported that the crew had found no problems that had not been anticipated.

The Russian Air Force

This chapter describes the development of the Russian Air Force. The author notes that bombing aircraft form a large percentage of the military aeroplanes owned by the Soviet Union.

This is the fifth article in the series on Air Fleets of the Nations.

Fighter Squadron Markings

FUSELAGE MARKINGS are shown in this colour plate, but the designs are repeated on the top planes as well (see inset picture). In some instances the design tapers with the fuselage to a point. The three designs in the bottom row are of Auxiliary Air Force squadrons. The coloured tailplane and fin of the Hawker Fury in the inset picture denote a flight commander of No. 25 Squadron. The lower aircraft is a Gloster Gauntlet of No. 19 Squadron.