© Wonders of World Aviation 2015-

Part 21

Part 21 of Wonders of World Aviation was published on Tuesday 26th July 1938, price 7d.

This part was the first in volume 2. It included a colour plate (acting as the frontispiece to volume 2) showing a Hawker Hind diving. This had previously appeared as the cover to Part 20.

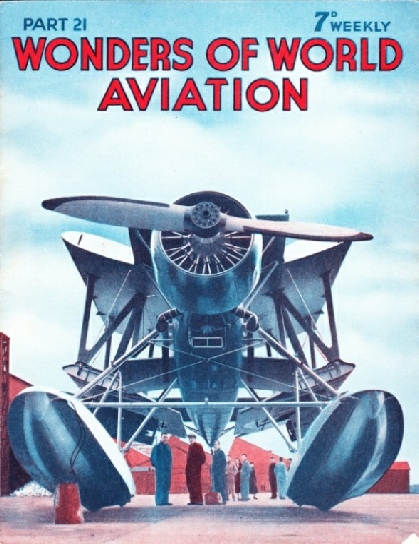

The Cover

This week’s cover shows one of the six Shark aeroplanes built by The Blackburn Aircraft Ltd, at Brough, Yorkshire, for the Portugues Navy. The Blackburn Shark bomber-reconnaissance seaplane is a staggered folding biplane, with a metal monocoque fuselage. The span is 46 feet, the length 35 ft 2 in, and the height 12 ft 1 in. The aircraft is powered by a 670- 700 horse-power Armstrong Siddeley fourteen-cylinder radial air-cooled engine . The maximum speed is 152 miles an hour at 5,500 feet and the alighting speed is 62 miles an hour.

A Hawker Hind Diving

THE SYNCHRONIZED GUNS fire through the propeller of the Hawker Hind, a light day bomber used in the Royal Air Force. These guns are accommodated in slots in the nose cowling of the aircraft. A third gun with flexible mounting is provided for the back cockpit to protect the machine from behind. Bomb racks are fitted on both sides of the fuselage below the bottom wings. Two 250-lb bombs can be carried, or a larger number of smaller ones. The pilot aims his two guns by pointing the aeroplane in the direction in which he wishes to fire. The Hawker Hind has a 640 horse-power Rolls-Royce Kestrel V water-cooled engine which gives the aeroplane a maximum speed of 187 miles an hour. The engine radiator is of the retractable type and is slung beneath the fuselage in front of the undercarriage.

Aircraft Armament

How the fighting powers of modern machines are continually being increased. This chapter deals with the armament of modern aircraft. Many authorities have maintained that progress in the development of the military aeroplane would be checked so that greater progress could be made with aeroplane armament.

Showman Who Turned Aviator

The flying of man-carrying kits was a prelude to “Colonel” Samuel Cody’s achievements with aeroplanes. Unlike so many makers of air history, he had had no engineering or scientific training, and his mechanical knowledge was comparatively negligible when he first became interested in aeronautics. This chapter tells the story of “Colonel” Cody.

This is the tenth article in the series on Makers of Air History.

Aerodrome Construction

The building of a modern aerodrome involves the cooperation of many widely different industries. Millions of pounds are being spent throughout the world on building new and improving existing aerodromes. The aerodrome constructor has to cope with a constant increase in the size, weight, power and numbers of aircraft, as well as providing equipment for aids to navigation.

British Airships

The story of British airships is of great fascination to all who are interested in lighter-than-air craft. This chapter traces the evolution of the airship in Great Britain from early experiments and the building of the first airship in 1907 until the tragedy of the R101 at Beauvais, France, in 1931.

This is the fourth article in the series on Airships.

Flight Sub-Lieutenant Warneford, VC

A biography of Sub-Lieutenant Reginald Warneford VC, who was the first pilot to bring down a German airship.

This chapter is the third article in the series on Epics of Service Flying.

Air Taxis (Part 1)

“By air to anywhere at any moment”. Such is the service rendered by the British charter companies which operate air taxis. Night and day, often at only a few minutes’ notice, an air taxi takes off for a flight of perhaps a hundred miles or for a flight of perhaps several thousand miles. This chapter fully describes the work of the air taxi. The article is concluded in part 22.