© Wonders of World Aviation 2015-

Part 39

Part 39 of Wonders of World Aviation was published on Tuesday 29th November 1938, price 7d.

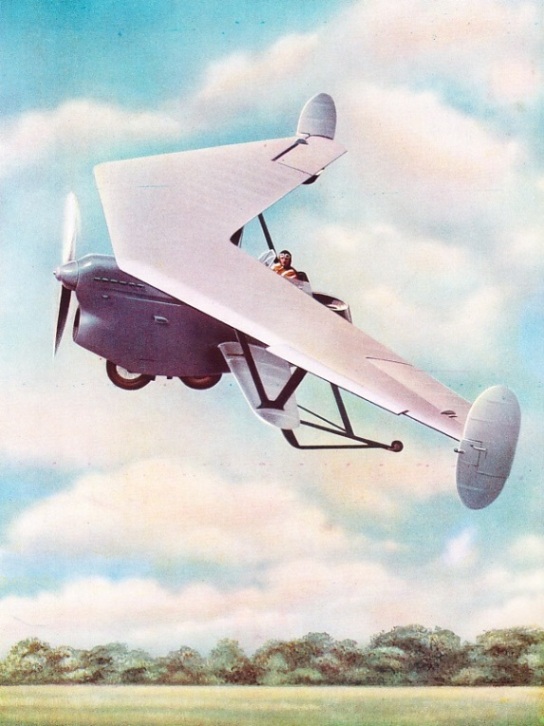

This part included a colour plate showing a two-seater pterodactyl aircraft . This was one of the illustrations in the article on Unconventional Aircraft.

The Cover

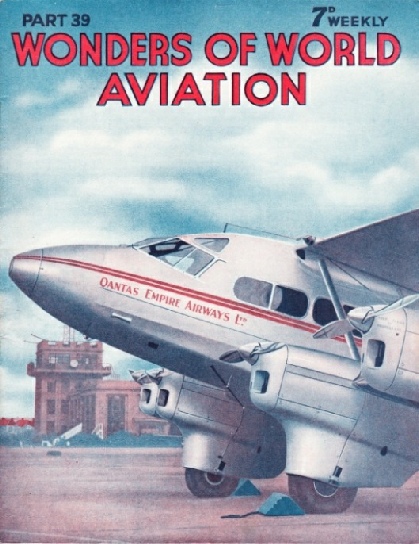

The cover on this week’s Part shows a four-engined De Havilland Express Air Liner belonging to Qantas Empire Airways, Ltd. This Australian company uses Express Air Liners between Darwin and Brisbane, and flying boats for the Singapore-Sydney service.

Contents of Part 39

A Spectacular Record Breaker (Part 2)

Unconventional Aircraft

Unconventional Aircraft (colour plate)

W. B. Rhodes-Moorhouse, VC

The Japanese Air Force

Tricycle Undercarriages

Aviation in India and Burma

The Second “Graf Zeppelin”

Hinkler - The Brilliant Navigator (Part 1)

William B. Rhodes-Moorhouse, VC

The life of William Barnard Rhodes-Moorhouse, VC , who was the first pilot to win the Victoria Cross.

This is the eighth article in the series Epics of Service Flying.

Unconventional Aircraft

This chapter deals with numerous highly interesting inventions. One of the earliest was that of Horatio F. Phillips, who produced in 1893 a multiplane flying machine that resembled a large Venetian blind. This steam-driven vehicle left the ground for a distance of 2,000 feet. It is reasonable to assume, had the internal combustion engine been sufficiently developed in 1893, that Phillips would have anticipated by ten years the achievements of the Wright brothers. An aircraft of highly original design was Clement Ader’s Avion, with its bat-like wings. This machine is stated - and denied - to have made a controlled flight in 1897. Whether it did or not, its name has been perpetuated in France; for avion is today the generic French term for all power-driven heavier-than-air craft. Other unconventional aircraft dealt with in this chapter include the “canard”, or tail-first aeroplane, the “Cyclogiro”, with paddle-wheels instead of airscrew or wings, and the tailless type, represented by the “Pterodactyl”.

Hinkler - The Brilliant Navigator (Part 1)

Bert Hinkler was a remarkable man. In an age when publicity is apparently inseparable from almost all human achievement, whether great or small, Hinkler’s unassuming manner and intense dislike of self-advertisement tended to make his brilliant achievements less important than in fact they were. Hinkler’s career as a long-distance flier began in 1920, in the era of the great pioneers such as Alcock and Brown, the brothers Ross and Keith Smith; and but for official interference Hinkler’s more important records might have begun at that time also. Even so, on his abortive attempt in 1920 to fly from England to Australia, he reached Turin, in the north of Italy, without a stop. This flight of about 700 miles was the longest hitherto made in a light aeroplane.

Hinkler had to wait eight years before he made his great flight to Australia. His was the first solo flight and the first light aeroplane flight from England to Australia. Hinkler’s remarkable achievements form the subject of this chapter which begins here and which concludes the series “Makers of Air History”.

This chapter is the eighteenth in the series Makers of Air History and concludes in part 40.

Tricycle Undercarriages

This chapter describes the tricycle undercarriage. This is a feature of aircraft design which improves performance and simplifies landing. However, the author also notes that, although the tricycle undercarriage is fitted as standard to one or two types of aircraft that are produced in small numbers, it is still in the experimental stage.

The Japanese Air Force

This chapter describes the development of the Japanese Air Force. The author notes that, like the United States, Japan has tended to concentrate upon naval air strength. The Japanese Army, however, has its own air force, which has made considerable progress in recent years. This is the sixth article in the series on Air Fleets of the Nations.

Unconventional Aircraft

A TWO-SEAT PTERODACTYL AIRCRAFT of fighter type powered by a water-cooled engine driving a tractor propeller. The first tailless aircraft was produced by J. W. Dunne in Scotland in 1911 and was successfully flown, After this the tailless aircraft was neglected until 1926, when Captain G. T. R. Hill produced his first tailless aeroplane. This first Pterodactyl was a single-seat light aeroplane driven by a pusher airscrew. The aileron controls of a Pterodactyl can be used in unison when it is desired to make the aircraft climb or dive. An American design of tailless aircraft has one semicircular wing in place

of two swept-back wings in the form of an arrowhead.

This illustration previously appeared on the front cover of Part 26.

Aviation in India and Burma

This chapter describes the development of aviation across India and Burma. The author notes that early flying development in India was slow, but that since 1932 internal airlines have rapidly increased.

This is the eighteenth article in the series on Air Routes of the World.

The Second “Graf Zeppelin”

This article describes the construction of LZ 130, Germany’s 119th Zeppelin, and named Graf Zeppelin.

Harry Hawker (Part 2)

The career of the Australian aviator Harry Hawker. This chapter shows that Hawker’s contributions to aviation were more important, particularly his work with the Sopwith Company, than his spectacular attempt to cross the North Atlantic Ocean.

This article is the eighteenth in the series Makers of Air History and is concluded from part 38.