© Wonders of World Aviation 2015-

Part 13

Part 13 of Wonders of World Aviation was published on Tuesday 31st May 1938, price 7d.

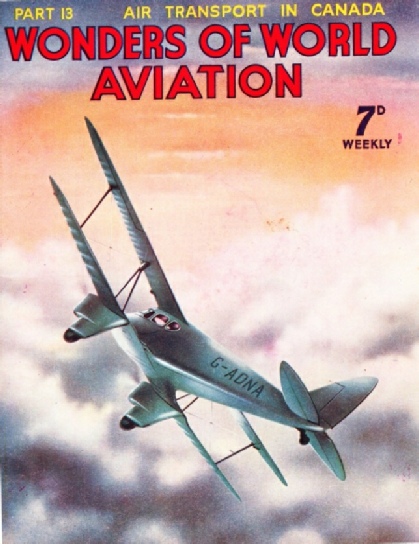

This part included a colour plate showing Henson’s proposed aeroplane. It formed part of the article on The First Powered Aeroplane.

The Cover

This week’s cover picture, from a Flight photograph, shows a De Havilland Dragonfly aircraft during a test flight. The Dragonfly seats five, and at sea level has a maximum speed of about 145 miles an hour.

Contents of Part 13

Geoffrey de Havilland (Part 2)

Progress to Solo Flying

Airscrews and Their Design

Air Transport in Canada

The London-Manchester Race

The First Powered Aeroplane

The First Powered Aeroplane (colour plate)

Representative Types of Continental and American Aircraft - 2

Tests of Flying Fitness (Part 1)

Geoffrey de Havilland (Part 2)

The story of Geoffrey de Havilland, a pioneer who, from small beginnings, has piloted his own machines to outstanding successes. This chapter is concluded from part 12.

It is the fifth article in the series on Makers of Air History.

Progress to Solo Flying

Before he is sent up for his first solo, the pupil may be taught spinning. Forced landings are seldom necessary these days because of the high degree of reliability of the modern aero engine. But it is necessary to be prepared for the thousandth chance. When the pupil has put in an hour or two solo, the instructor will prepare him for the practical flying tests necessary for obtaining the “A” licence.

This chapter is the fourth article in the series on Learning to Fly.

Airscrews and Their Design

The airscrew is the mechanism which converts the engine energy into the work which has to be done to drive the aeroplane against the air resistance due to its motion. This chapter describes all aspects of airscrews and their design.

Air Transport in Canada

How the aeroplane has brought speedy travel and transport facilities to this northern Dominion. This chapter tells how Canada leads the world in the transport of freight by air. Canada’s aviation has progressed to a high standard of efficiency without a subsidy and with little help from the Government.

This is the fifth article in the series Air Routes of the World.

The London-Manchester Race

After Louis Bleriot had won in 1909 the Daily Mail prize for the first aeroplane across the English Channel, that journal offered a cash prize of £10,000 for the first aviator to fly from London to Manchester. A start had to be made from a place within five miles of the Daily Mail’s London office, and the finish had to be within a similar distance of the newspaper’s Manchester office. The flight had to be completed within twenty-four hours, and only two landings were allowed, for fuel and any necessary adjustments to the machine or engine.

This chapter is the fifth article in the series on Great Flights.

The First Powered Aeroplane

A manufacturer of lace machinery was destined to become famous as the inventor of the first aeroplane to fly under its own power. The lace machinery manufacturer was John Stringfellow. One day in 1820 Stringfellow me a young engineer named William Samuel Henson. For years Henson had been ambitious to solve the great problem of flight. With their common engineering interests, they soon became firm friends. This chapter describes the development of their ideas.

The Aeroplane Proposed by Henson in 1842

THE AEROPLANE PROPOSED BY HENSON in his patent of 1842. Power was to be obtained from a light steam engine to drive paddle wheels or other propellers. The design was for a huge monoplane built of bamboo and hollow wooden spars braced with wires. This illustration shows the completed machine as seen from below, and the framework of the machine as seen from above. There are three spars running the whole length of the wings. The centre spar is of rectangular section; the outer two are of oval section and taper towards their ends. Sections at the centres and ends of the tapering spars are shown in the inset. This inset also shows plan and side views of a turnbuckle used to tighten the bracing wires.

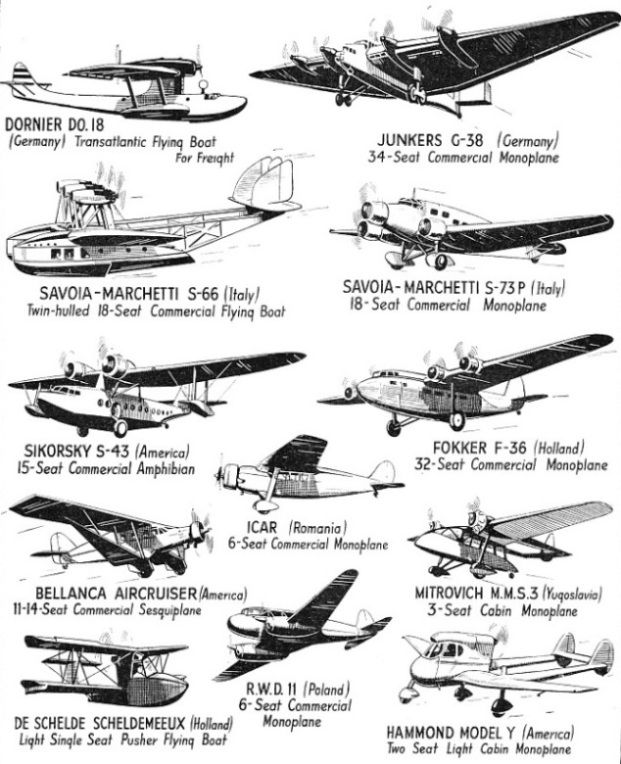

Representative Types of Continental and American Aircraft - 2

The previous diagram appeared in Part 12.

Tests of Flying Fitness (Part 1)

There is no recorded instance in the history of British aviation of an accident due to the physical failure of a commercially-licensed pilot. This is largely due to the high standard of physical fitness demanded in the specialized examinations of the Central Medical Board of the Air Ministry. This Board has to ensure that none but pilots of exceptional fitness are licensed commercially to carry passengers or goods by air. This chapter is concluded in part 14.